I knew this would get harder in wintertime—I just underestimated how hard by a long shot. By many long shots, actually.

The weight of the Northwest winters in the before (COVID) times were bleak enough to make one not want to get out of bed, let alone swim in icy water.

And I wasn’t open water swimming in winters past—

And there wasn’t a global pandemic in winters past.

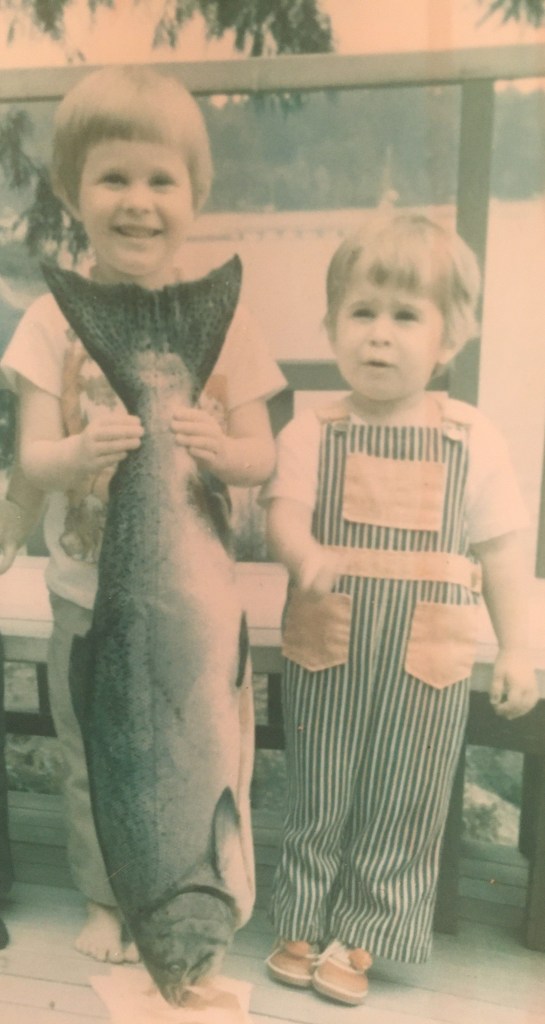

My youngest son is to thank for getting me to swim today—my first actual swim of 2021. My mood was as dark as the seaweed swirling below me, and after a gentle nudge from my son that “maybe a swim” would help, and after a couple hours avoiding the idea, I gave in.

He was right. The swim did help.

In fact my mood lightened as soon as I pulled my black plastic dog poop bag over my foot to ease the task of pulling on my snug wetsuit.

In my defense, I was anticipating dirty water from the endless rain of late and fretting about sewage spills, and weighing the risk/benefit ratio. In neighboring King County there were several warnings, and just the other side of the island an entire harbor is listed as “no contact” due to sewage overflow.

This is enough sad news alone to give one pause to open water swimming—and cause heartache. And the other night my husband and I watched a nature documentary with David Attenborough narrating the plight of the melting polar ice caps. We sat motionless watching as enormous walruses went cascading down to their deaths, forced to climb up to unnatural heights to find space to be ashore, as their former icy islands have shrunk by 40%. Rarely do I watch t.v., and even more rarely do I cry watching a show. Tears rolled down my face. And the next afternoon, my husband mentioned the walruses again. A lump grew in my throat.

I am afraid that I didn’t think as much about the Salish Sea and all of the other waterways of the world as I do now. One can’t spend time in a place like this and not fall in love. And loving it means thinking a lot about how to save it. Writing and sharing my stories is one small way I hope to bring awareness to our dependence on this place and the huge responsibility we have to making changes—even small ones to lesson our impact and preserve the infinite life within.

The beauty out there is the wildness. The blustery wind and the choppy waves and the honest cold. And the millions of lives living just out of view below the surface or miles down where no light ever goes.

As swimmers, we ride the surface, skimming barely over the vast world beneath us. There is no softening the sensation of the cold for the bare parts exposed directly to the water.

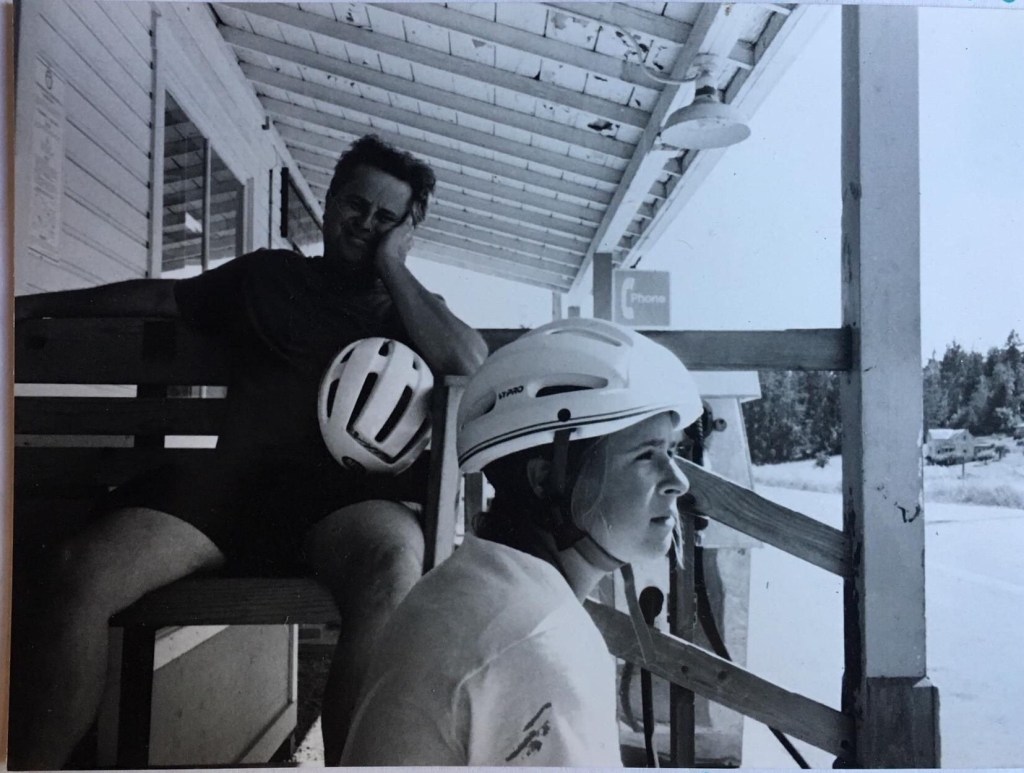

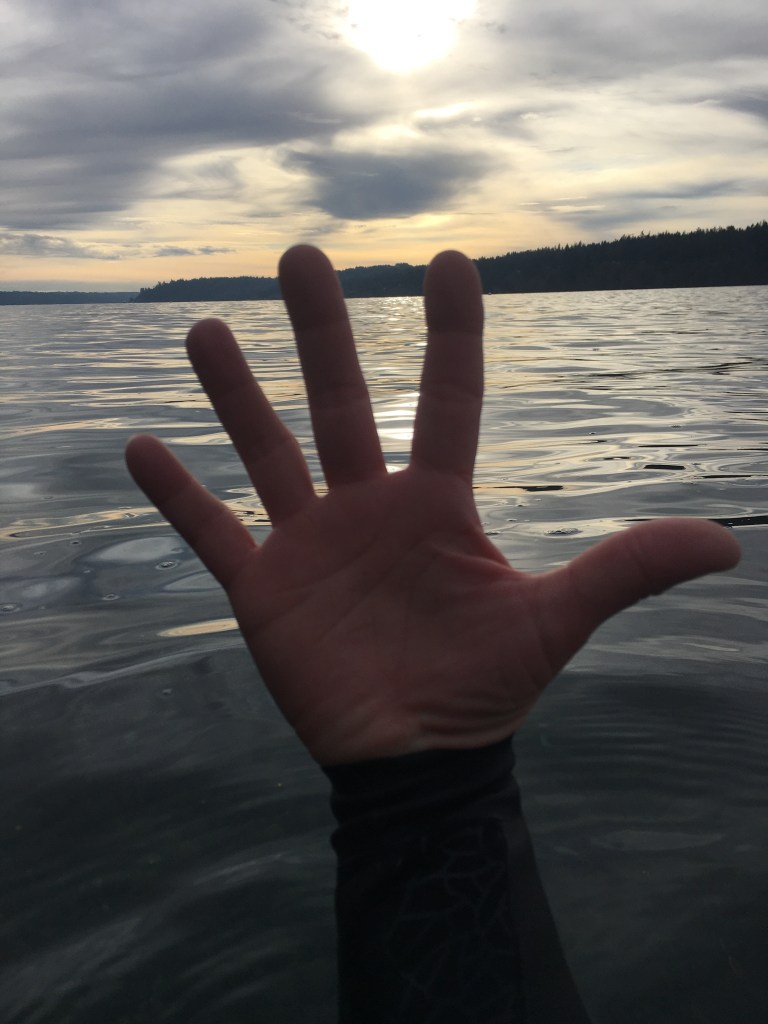

This afternoon I stood chest deep and splashed wildly about to wet my face and acclimate my hands, as both refused to plunge in the normal way. I turned northward, and spotted my eldest son on the beach. I splashed toward him and he got out his phone for a picture.

I waved goodbye, and in time my frigid hands adjusted, my face flushed with the exertion and my body eased. The water was murky, but the inner lift I felt bouncing along over the waves was well worth it. Once home there was a shower waiting. I could wash away the salt, but the experience would stay and it was a good one. My body rocked about, at ease again, floating in saltwater. I got a sudden strong whiff of salt—the smell of summer—and for a split second I was transported to the summer, and was reminded of the light and the warmth that will return in time.

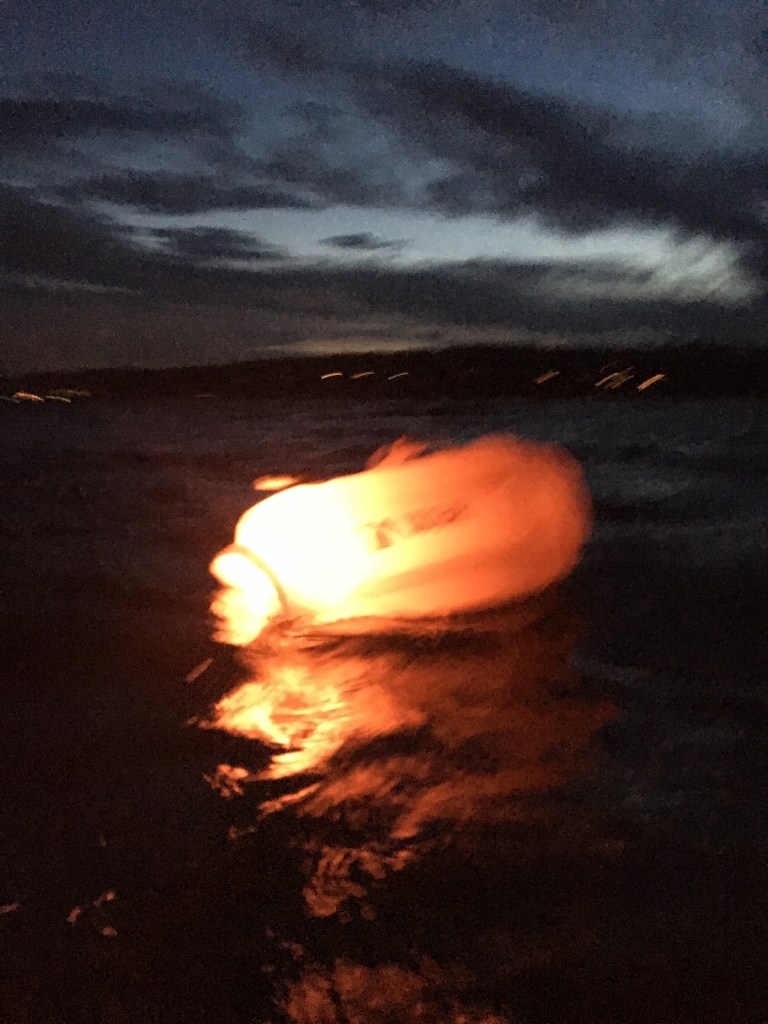

The sky grew dark as I arrived back at the landing, and clutching my glowing swim buoy I floated for a moment. To the south I spotted the small float where just yesterday I watched a family of river otters tumble about as large waves rocked them up and down.

And I thought again of the walruses. They don’t have enough space to cavort and rest and mate, like the otters and me.

On the flip side they have an impressive amount of blubber to keep them warm. I wonder if they ever get really cold and tire of the dark days of winter.

I suspect they are just fighting to survive.